The SCV version of 'belief' in 'Black Confederates'

- Thread starter jgoodguy

- Start date

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

First up is

https://scv.org/contributed-works/black-confederates/

Black Confederates

Why haven’t we heard more about them? National Park Service historian, Ed Bearrs, stated, “I don’t want to call it a conspiracy to ignore the role of Blacks both above and below the Mason-Dixon line, but it was definitely a tendency, which began around 1910.” Historian, Erwin L. Jordan, Jr., calls it a “cover-up” which started back in 1865. He writes, “During my research, I came across instances where Black men stated they were soldiers, but you can plainly see where ‘soldier’ is crossed out and ‘body servant’ inserted, or ‘teamster’ on pension applications.” Another black historian, Roland Young, says he is not surprised that blacks fought. He explains that “…some, if not most, Black southerners would support their country” and that by doing so they were “demonstrating it’s possible to hate the system of slavery and love one’s country.” This is the very same reaction that most African Americans showed during the American Revolution, where they fought for the colonies, even though the British offered them freedom if they fought for them.

It has been estimated that over 65,000 Southern blacks were in the Confederate ranks. Over 13,000 of these, “saw the elephant” also known as meeting the enemy in combat. These Black Confederates included both slave and free. The Confederate Congress did not approve blacks to be officially enlisted as soldiers (except as musicians), until late in the war. But in the ranks it was a different story. Many Confederate officers did not obey the mandates of politicians, they frequently enlisted blacks with the simple criteria; “Will you fight?” Historian Ervin Jordan, explains that “biracial units” were frequently organized “by local Confederate and State militia Commanders in response to immediate threats in the form of Union raids…”. Dr. Leonard Haynes, an African-American professor at Southern University, stated, “When you eliminate the black Confederate soldier, you’ve eliminated the history of the South.”

Charles Kelly Barrow, et. al. Forgotten Confederates: An Anthology About Black Southerners (1995). Currently the best book on the subject.

Ervin L. Jordan, Jr. Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia (1995). Well researched and very good source of information on Black Confederates, but has a strong Union bias.

Richard Rollins. Black Southerners in Gray (1994). Also an excellent source.

Dr. Edward Smith and Nelson Winbush, “Black Southern Heritage”. An excellent educational video. Mr. Winbush is a descendent of a Black Confederate and a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV).

This fact sheet is provided by Scott Williams. It is not an all-inclusive list of Black Confederates, only a small sampling of accounts. For more information about the SCV or “Confederates of Color” contact Mr. Williams at e-mail: swcelt@stlnet.com.

For general historical information on Black Confederates, contact Dr. Edward Smith, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20016; Dean of American Studies. Dr. Smith is a black professor dedicated to clarifying the historical role of African Americans.

https://scv.org/contributed-works/black-confederates/

Black Confederates

Why haven’t we heard more about them? National Park Service historian, Ed Bearrs, stated, “I don’t want to call it a conspiracy to ignore the role of Blacks both above and below the Mason-Dixon line, but it was definitely a tendency, which began around 1910.” Historian, Erwin L. Jordan, Jr., calls it a “cover-up” which started back in 1865. He writes, “During my research, I came across instances where Black men stated they were soldiers, but you can plainly see where ‘soldier’ is crossed out and ‘body servant’ inserted, or ‘teamster’ on pension applications.” Another black historian, Roland Young, says he is not surprised that blacks fought. He explains that “…some, if not most, Black southerners would support their country” and that by doing so they were “demonstrating it’s possible to hate the system of slavery and love one’s country.” This is the very same reaction that most African Americans showed during the American Revolution, where they fought for the colonies, even though the British offered them freedom if they fought for them.

It has been estimated that over 65,000 Southern blacks were in the Confederate ranks. Over 13,000 of these, “saw the elephant” also known as meeting the enemy in combat. These Black Confederates included both slave and free. The Confederate Congress did not approve blacks to be officially enlisted as soldiers (except as musicians), until late in the war. But in the ranks it was a different story. Many Confederate officers did not obey the mandates of politicians, they frequently enlisted blacks with the simple criteria; “Will you fight?” Historian Ervin Jordan, explains that “biracial units” were frequently organized “by local Confederate and State militia Commanders in response to immediate threats in the form of Union raids…”. Dr. Leonard Haynes, an African-American professor at Southern University, stated, “When you eliminate the black Confederate soldier, you’ve eliminated the history of the South.”

- The “Richmond Howitzers” were partially manned by black militiamen. They saw action at 1st Manassas (or 1st Battle of Bull Run) where they operated battery no. 2. In addition two black “regiments”, one free and one slave, participated in the battle on behalf of the South. “Many colored people were killed in the action”, recorded John Parker, a former slave.

- At least one Black Confederate was a non-commissioned officer. James Washington, Co. D 34th Texas Cavalry, “Terrell’s Texas Cavalry” became it’s 3rd Sergeant. In comparison, The highest-ranking Black Union soldier during the war was a Sergeant Major.

- Free black musicians, cooks, soldiers and teamsters earned the same pay as white confederate privates. This was not the case in the Union army where blacks did not receive equal pay. At the Confederate Buffalo Forge in Rockbridge County, Virginia, skilled black workers “earned on average three times the wages of white Confederate soldiers and more than most Confederate army officers ($350-$600 a year).

- Dr. Lewis Steiner, Chief Inspector of the United States Sanitary Commission while observing Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson’s occupation of Frederick, Maryland, in 1862: “Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number

[Confederate troops]. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc., and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederate Army.”

- Frederick Douglas reported, “There are at the present moment many Colored men in the Confederate Army doing duty not only as cooks, servants and laborers, but real soldiers, having musket on their shoulders, and bullets in their pockets, ready to shoot down any loyal troops and do all that soldiers may do to destroy the Federal government and build up that of the rebels.”

- Black and white militiamen returned heavy fire on Union troops at the Battle of Griswoldsville (near Macon, GA). Approximately 600 boys and elderly men were killed in this skirmish.

- In 1864, President Jefferson Davis approved a plan that proposed the emancipation of slaves, in return for the official recognition of the Confederacy by Britain and France. France showed interest but Britain refused.

- The Jackson Battalion included two companies of black soldiers. They saw combat at Petersburg under Col. Shipp. “My men acted with utmost promptness and goodwill…Allow me to state sir that they behaved in an extraordinary acceptable manner.”

- Recently the National Park Service, with a recent discovery, recognized that blacks were asked to help defend the city of Petersburg, Virginia and were offered their freedom if they did so. Regardless of their official classification, black Americans performed support functions that in today’s army many would be classified as official military service. The successes of white Confederate troops in battle, could only have been achieved with the support these loyal black Southerners.

- Confederate General John B. Gordon (Army of Northern Virginia) reported that all of his troops were in favor of Colored troops and that it’s adoption would have “greatly encouraged the army”. Gen. Lee was anxious to receive regiments of black soldiers. The Richmond Sentinel reported on 24 Mar 1864, “None…will deny that our servants are more worthy of respect than the motley hordes, which come against us.” “Bad faith [to black Confederates] must be avoided as an indelible dishonor.”

- In March 1865, Judah P. Benjamin, Confederate Secretary Of State, promised freedom for blacks that served from the State of Virginia. Authority for this was finally received from the State of Virginia and on April 1st 1865, $100 bounties were offered to black soldiers. Benjamin exclaimed, “Let us say to every Negro who wants to go into the ranks, go and fight, and you are free…Fight for your masters and you shall have your freedom.” Confederate Officers were ordered to treat them humanely and protect them from “injustice and oppression”.

- A quota was set for 300,000 black soldiers for the Confederate States Colored Troops. 83% of Richmond’s male slave population volunteered for duty. A special ball was held in Richmond to raise money for uniforms for these men. Before Richmond fell, black Confederates in gray uniforms drilled in the streets. Due to the war ending, it is believed only companies or squads of these troops ever saw any action. Many more black soldiers fought for the North, but that difference was simply a difference because the North instituted this progressive policy more soon than the more conservative South. Black soldiers from both sides received discrimination from whites that opposed the concept.

- Union General U.S. Grant in Feb 1865, ordered the capture of “all the Negro men… before the enemy can put them in their ranks.” Frederick Douglas warned Lincoln that unless slaves were guaranteed freedom (those in Union controlled areas were still slaves) and land bounties, “they would take up arms for the rebels”.

- On April 4, 1865 (Amelia County, VA), a Confederate supply train was exclusively manned and guarded by black Infantry. When attacked by Federal Cavalry, they stood their ground and fought off the charge, but on the second charge they were overwhelmed. These soldiers are believed to be from “Major Turner’s” Confederate command.

- A Black Confederate, George _____, when captured by Federals was bribed to desert to the other side. He defiantly spoke, “Sir, you want me to desert, and I ain’t no deserter. Down South, deserters disgrace their families and I am never going to do that.”

- Former slave, Horace King, accumulated great wealth as a contractor to the Confederate Navy. He was also an expert engineer and became known as the “Bridge builder of the Confederacy.” One of his bridges was burned in a Yankee raid. His home was pillaged by Union troops, as his wife pleaded for mercy.

- As of Feb. 1865 1,150 black seamen served in the Confederate Navy. One of these was among the last Confederates to surrender, aboard the CSS Shenandoah, six months after the war ended. This surrender took place in England.

- Nearly 180,000 Black Southerners, from Virginia alone, provided logistical support for the Confederate military. Many were highly skilled workers. These included a wide range of jobs: nurses, military engineers, teamsters, ordnance department workers, brakemen, firemen, harness makers, blacksmiths, wagonmakers, boatmen, mechanics, wheelwrights, etc. In the 1920’S Confederate pensions were finally allowed to those workers that were still living. Many thousands more served in other Confederate States.

- During the early 1900’s, many members of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) advocated awarding former slaves rural acreage and a home. There was hope that justice could be given those slaves that were once promised “forty acres and a mule” but never received any. In the 1913 Confederate Veteran magazine published by the UCV, it was printed that this plan “If not Democratic, it is [the] Confederate” thing to do. There was much gratitude toward former slaves, which “thousands were loyal, to the last degree”, now living with total poverty of the big cities. Unfortunately, their proposal fell on deaf ears on Capitol Hill.

- During the 5oth Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913, arrangements were made for a joint reunion of Union and Confederate veterans. The commission in charge of the event made sure they had enough accommodations for the black Union veterans, but were completely surprised when unexpected black Confederates arrived. The white Confederates immediately welcomed their old comrades, gave them one of their tents, and “saw to their every need”. Nearly every Confederate reunion including those blacks that served with them, wearing the gray.

- The first military monument in the US Capitol that honors an African-American soldier is the Confederate monument at Arlington National cemetery. The monument was designed 1914 by Moses Ezekiel, a Jewish Confederate, who wanted to correctly portray the “racial makeup” in the Confederate Army. A black Confederate soldier is depicted marching in step with white Confederate soldiers. Also shown is one “white soldier giving his child to a black woman for protection”. – Source: Edward Smith, African American professor at the American University, Washington DC.

- Black Confederate heritage is beginning to receive the attention it deserves. For instance, Terri Williams, a black journalist for the Suffolk “Virginia Pilot” newspaper, writes: “I’ve had to re-examine my feelings toward the [Confederate] flag…It started when I read a newspaper article about an elderly black man whose ancestor worked with the Confederate forces. The man spoke with pride about his family member’s contribution to the cause, was photographed with the [Confederate] flag draped over his lap…that’s why I now have no definite stand on just what the flag symbolizes, because it no longer is their history, or my history, but our history.”

Charles Kelly Barrow, et. al. Forgotten Confederates: An Anthology About Black Southerners (1995). Currently the best book on the subject.

Ervin L. Jordan, Jr. Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia (1995). Well researched and very good source of information on Black Confederates, but has a strong Union bias.

Richard Rollins. Black Southerners in Gray (1994). Also an excellent source.

Dr. Edward Smith and Nelson Winbush, “Black Southern Heritage”. An excellent educational video. Mr. Winbush is a descendent of a Black Confederate and a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV).

This fact sheet is provided by Scott Williams. It is not an all-inclusive list of Black Confederates, only a small sampling of accounts. For more information about the SCV or “Confederates of Color” contact Mr. Williams at e-mail: swcelt@stlnet.com.

For general historical information on Black Confederates, contact Dr. Edward Smith, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20016; Dean of American Studies. Dr. Smith is a black professor dedicated to clarifying the historical role of African Americans.

5fish

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jul 28, 2019

- Messages

- 10,737

- Reaction score

- 4,569

I found this about the Confederate Navy and Marines...

http://www.navyandmarine.org/ondeck/1862blackCSN.htm

Dr. Edward Smith, Dean of American Studies at American University, estimates that by February 1865, 1,150 Black Americans had served in the Confederate States Navy. This number would equate to approximately 20 percent of this branch of the Confederate military.

Confederate Naval Regulations allowed a ship’s captain a ratio of one black seaman to five white seamen. A higher percentage of black crewmen were allowed upon the captain filing an exemption. Since numerous exemptions were filed, it seems reasonable to conclude that the surface has barely been scratched where blacks in the Confederate Navy are concerned.

Most of the Confederate States Marine Corps records were intentionally destroyed at the end of the war, less they fall into enemy hands. As a result, research of any kind into this branch of service is very much a challenge. What follows are the names and descriptions of Black Americans I have been able to positively identify as having served with the Confederate States Navy and Marine Corps.

The linked has details and names...

http://www.navyandmarine.org/ondeck/1862blackCSN.htm

Dr. Edward Smith, Dean of American Studies at American University, estimates that by February 1865, 1,150 Black Americans had served in the Confederate States Navy. This number would equate to approximately 20 percent of this branch of the Confederate military.

Confederate Naval Regulations allowed a ship’s captain a ratio of one black seaman to five white seamen. A higher percentage of black crewmen were allowed upon the captain filing an exemption. Since numerous exemptions were filed, it seems reasonable to conclude that the surface has barely been scratched where blacks in the Confederate Navy are concerned.

Most of the Confederate States Marine Corps records were intentionally destroyed at the end of the war, less they fall into enemy hands. As a result, research of any kind into this branch of service is very much a challenge. What follows are the names and descriptions of Black Americans I have been able to positively identify as having served with the Confederate States Navy and Marine Corps.

The linked has details and names...

Andersonh1

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 13, 2019

- Messages

- 580

- Reaction score

- 742

I was present when Dr. Walter Curry was giving a talk on his ancestor, Lavinia Corley Thompson, and he said much the same thing, that there was a "conspiracy" to remove these men from the historical record. I'd love to have had more details.Why haven’t we heard more about them? National Park Service historian, Ed Bearrs, stated, “I don’t want to call it a conspiracy to ignore the role of Blacks both above and below the Mason-Dixon line, but it was definitely a tendency, which began around 1910.” Historian, Erwin L. Jordan, Jr., calls it a “cover-up” which started back in 1865. He writes, “During my research, I came across instances where Black men stated they were soldiers, but you can plainly see where ‘soldier’ is crossed out and ‘body servant’ inserted, or ‘teamster’ on pension applications.”

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

'Conspiracy theories' are a form of 'belief'.I was present when Dr. Walter Curry was giving a talk on his ancestor, Lavinia Corley Thompson, and he said much the same thing, that there was a "conspiracy" to remove these men from the historical record. I'd love to have had more details.

Conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation of an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful actors, often political in motivation,[2][3] when other explanations are more probable.[4] The term has a pejorative connotation, implying that the appeal to a conspiracy is based on prejudice or insufficient evidence.[5] Conspiracy theories resist falsification and are reinforced by circular reasoning: both evidence against the conspiracy and an absence of evidence for it, are re-interpreted as evidence of its truth,[5][6] and the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than proof.[7][8]

5fish

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jul 28, 2019

- Messages

- 10,737

- Reaction score

- 4,569

Link:https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-warAt least one Black Confederate was a non-commissioned officer. James Washington, Co. D 34th Texas Cavalry, “Terrell’s Texas Cavalry” became it’s 3rd Sergeant. In comparison, The highest-ranking Black Union soldier during the war was a Sergeant Major.

This person above was incorrect about the highest-ranking Black Union soldier... The Native Guard was originally led by Black officers...

By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause. There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman (photo citation: 200-HN-PIO-1), who scouted for the 2d South Carolina Volunteers.

Last edited:

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

There are lots of problems, but what it is, is evidence of a 'belief ' or 'myth'.This person above was incorrect about the highest-ranking Black Union soldier... The Native Guard was originally led by Black officers...

By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause. There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman (photo citation: 200-HN-PIO-1), who scouted for the 2d South Carolina Volunteers.

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

https://scv.org/contributed-works/the-role-of-black-soldiers-in-the-confederate-army/

Home/Contributed Works/The Role of Black Soldiers in the Confederate Army

By SSG Harry W. Tison, II

Many historians would have you believe that all minority groups such as Blacks, Indians, and Hispanics hated the Confederacy and what it stood for. This is completely untrue according to records that are recently been brought to the forefront of history. Groups such as the 37th Texas Calvary and the Sons of Confederate Veterans have for many years tried to make this information possible. For those who do not know, the 37th Texas Calvary is a Civil War reenactment group that prides itself on having minorities in their unit. The Sons of Confederate Veterans is a historical group only. There are men of color within this group and they are very proud of their heritage.

Why then have we not heard of these proud soldiers? The answer may lie in the fact that many of the history books that are in our schools were written by people who are either ignorant of the situation or by someone bent on covering up the true history of the past. I have found a lot of information about these soldiers on the Internet and have even met some of the blacks in the Sons of Confederate Veterans. This paper is to bring out the truth about them with the hopes that others will see exactly wha t the War of Northern Aggression was about.

First, the war was not 100% about slavery. Yes, there was a small portion of people in the South that owned slaves and thought that there was nothing wrong with it. But the majority of people believed that the North was oppressing them much the same way that the King of England was oppressing their parents and grandparents were in the Revolutionary War. The North was trying to put heavy taxes on things such as cotton, tobacco and other such items that the South was producing. Although very difficult, the way of life in the South was a matter of pride and not to be messed around with.

Although blacks were repressed in the South, the same was true in the North. Blacks were probably discriminated against in New York City and Boston more than they were in Charleston or Atlanta. Yes, they were ‘free’ in the North, but were still considered second-class citizens to many in the North. They still did not have the right to vote nor were they allowed in the same establishments as whites. This is why the majority of blacks stayed in the South when the war started. They stayed to fight for their homeland against the ‘Yankees’. There was between 50,000 to 100,000 blacks that served in the Confederate Army as cooks, blacksmiths, and yes, even soldiers. Hollywood would have us believe that the Union Army first started letting Blacks fight with the movie “Glory”, the story of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. This is not the case. Here is the history of these brave souls.

There are many references to the trials that blacks had to endure during this era. Not many though, tell the story of blacks that served in the Confederacy. Although it is true that a good number of slaves fled to the North, there were those that chose to stay in the South to stay with their families or to fight what they saw as the tyranny of the Yankees. There is the story of a slave whose name were Silas Chandler and his master Andrew Chandler. (www.37thtexas.org) Andrew enlisted in the 44th Mississippi Volunteer Regiment and took Silas along with him as many Southerners did. Andrew was 15 years old and Silas was nearly 17 and very close friends with Andrew. Silas traveled between the plantation in Mississippi and wherever Andrew was. Andrew wrote home on 31 Aug 1862, “If the Feds were to capture him, they might take him along with them.” “I greatly fear another raid, don’t let them catch Silas. Be sure to write when Silas gets home.”

Andrew was severely wounded in the Battle of Chickamauga. Army doctors were prepared to amputate his leg but Silas refused to let the doctors perform the operation. Instead, he used a piece of gold to buy whiskey, which he used to buy a bottle of whiskey to bribe the surgeons for Andrews release. He carried his master on his back and loaded him on a boxcar in Atlanta and better medical care. Andrew survived as a cripple and the two remained friends for the rest of their lives and both received pensions for serving in the war.

On the far side of Arlington National Cemetery, in a little known place, is the cemetery’s largest monument. It is the Confederate Memorial that stands over the graves of Confederate Soldiers. On this monument is a carving of a black soldier, not in chains, but in a Confederate uniform marching along side his fellow soldiers. The sculptor of this monument was Moses Ezekiel. A Confederate veteran who knew what the true history of the war was. Ezekiel himself was a minority in the Confederate Army being Jewish, so he knew some of the trials the blacks were facing in the country. He was a native Virginian who graduated from the Virginia Military Institute and fought in the Battle of New Market where several black Confederates saw action. (www.37thtexas.org)

Although the Confederates did not officially enlist blacks until March 1865, some states allowed them to serve on a local level as early as 1861. Nobody really knows how many blacks actually served in the Confederacy; some estimates go as high as 50,000. A Union officer noted in his diary shortly before the Battle of Sharpsburg:

“Wednesday, September 10: At 4 o’clock this morning the Rebel army began to move from our town, (Fredrick, Md), Jackson’s forces taking the advance. The movement continued until 8 o’clock pm, occupying 16 hours. The most liberal calculation could not give them more than 64,000 men. Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. They were supplied with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc and they were an integral portion of the Southern Confederate army. They were seen riding on horses and mules, driving wagons, riding on caissons, in ambulances, with the staff of generals and promiscuously mixing it up with all the Rebel horde.” (Union Sanitation Commission Inspector Dr. Louis Steiner, Sept. 1862.)

Another Black Confederate is Levi Miller, a former slave who became a Confederate hero. He was one of thousands of slaves who went to war with their masters as a body servant. He was voted by his regiment to be a full-fledge soldier after nursing his master back from a near fatal wound. He also exhibited bravery in battles in Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. During the fighting at Spotsylvania Courthouse, his former commander, Capt. J.E. Anderson, said of him, “Levi Miller stood by my side and no man fought harder and better than he did when the enemy tried to cross our little breastworks and we clubbed and bayoneted them off, no one used his bayonet with more skill and effect than Levi Miller. During several battles, Levi met several other Negroes that he knew either by friendship or as a relative. They attempted to get him to desert to the North, but would not.

Upon his death, it is ironic that his coffin was draped with the Stars and Bars at a hero’s funeral service. He was laid to rest in a black cemetery. This is perhaps the biggest irony of all since the cemetery is near the spot where R.E. Lee is buried.

In a letter dated 27 March 1865, Lt. Col. Charles Marshall wrote a letter to Lt. Gen. Ewell stating that Gen. Lee regretted the “unwillingness of owners to permit their slaves to enter the service”, and “His only objection to calling them colored troops was that the enemy had selected that designation for theirs”. Also, “Harshness and contemptuous or offensive language or conduct to them must be forbidden and they should forget as soon as possible that they were regarded as menials”.

The following is a list of 4 soldiers captured at Ft. Fisher when it fell to Union troops in January 1865:

Charles Dempsey, Private, Company F, 36th NC Regiment, Negro. Captured at Ft. Fisher and confined at Point Lookout, Md., until paroled and exchanged at Coxes Landing, Va. 14-15 Feb 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

Henry Dempsey, Private, Company F, 36th NC Regiment, Negro. Captured at Ft. Fisher and confined at Point Lookout, Md., until paroled at Coxes Landing, Va. 14-15 Feb 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

J. Doyle, Private, Company E, 40th NC Regiment, Negro, Captured at Ft. Fisher and confined at Point Lookout, Md., until paroled at Boulware’s Wharf, Va. On 16 Mar 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

Daniel Herring, Cook, Company F, 36th NC Regiment, Negro. Captured at Ft. Fisher, and confined at Point Lookout, Md. Until released after taking Oath of Allegiance June 19, 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

Notice that all 4 soldiers were black and that one of them signed an Oath of Allegiance only after Lee’s surrender.

If you look at the make up of Union troops, you can plainly see that blacks were segregated into separate units, while in the South, they were mixed in with the white troops. They were also given the same pay and rations as other Confederate troops as opposed to their counterparts in the North. In June 1861, Tennessee became the first state in the South to allow the use of black soldiers. The governor authorized the enrollment of those between the ages of 15-50 and have the same rations and clothing as white soldiers. Blacks started appearing in Tennessee regiments by September of that same year.

At the Battle of Fair Oaks near Richmond, a black cook and minister with the Alabama regiment picked up a rifle and was heard yelling, “Der Lor’ hab mercy on us all, boys, here dey comes agin!” As the Alabamians returned fire and mounted a charge, he was heard shouting, “Pitch in white folks, Uncle Pomp’s behind yer. Send them Yankees to de ‘ternal flames!” (Battlefields of the South. Vol. 2, page 253)

There are many stories about Black Confederates. I have listed only a few to give you a glimpse at them. There are many resources to go to and read if you wish to learn more. History can no longer be covered up by the ‘do-gooders’ that wish to wash our minds of the truth. I know where the hatred for the Confederate Battle Flag comes from, and it is not from the Old Confederacy. It comes from those who chose to degrade the good names of Confederate Soldiers. What they don’t realize though is that what they are hiding behind in the name of racial purity was fought and died for by men of all races; including blacks.

BIBILOGRAPHY FOR ROLES OF BLACKS IN THE CONFEDERATE ARMY

www.37thtexas.org. – The Black and the Gray

Washington City Paper-July 17, 1998

Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia by Ervin L. Jordan, Jr. (Charlottesville, Va: University Press of Virginia

Calico, Black and Gray: Women and Blacks in the Confederacy by Edward C. Smith, Civil War Magazine, Vol. VIII, No. 3, Issue XXIII, pg. 14

Battlefields of the South – Vol. 2

North Carolina Troops, Volume I

The Official Louisiana Tourism website – www.crt.state.la.us/crt/tourism/civilwar/overview.htm

Home/Contributed Works/The Role of Black Soldiers in the Confederate Army

By SSG Harry W. Tison, II

Many historians would have you believe that all minority groups such as Blacks, Indians, and Hispanics hated the Confederacy and what it stood for. This is completely untrue according to records that are recently been brought to the forefront of history. Groups such as the 37th Texas Calvary and the Sons of Confederate Veterans have for many years tried to make this information possible. For those who do not know, the 37th Texas Calvary is a Civil War reenactment group that prides itself on having minorities in their unit. The Sons of Confederate Veterans is a historical group only. There are men of color within this group and they are very proud of their heritage.

Why then have we not heard of these proud soldiers? The answer may lie in the fact that many of the history books that are in our schools were written by people who are either ignorant of the situation or by someone bent on covering up the true history of the past. I have found a lot of information about these soldiers on the Internet and have even met some of the blacks in the Sons of Confederate Veterans. This paper is to bring out the truth about them with the hopes that others will see exactly wha t the War of Northern Aggression was about.

First, the war was not 100% about slavery. Yes, there was a small portion of people in the South that owned slaves and thought that there was nothing wrong with it. But the majority of people believed that the North was oppressing them much the same way that the King of England was oppressing their parents and grandparents were in the Revolutionary War. The North was trying to put heavy taxes on things such as cotton, tobacco and other such items that the South was producing. Although very difficult, the way of life in the South was a matter of pride and not to be messed around with.

Although blacks were repressed in the South, the same was true in the North. Blacks were probably discriminated against in New York City and Boston more than they were in Charleston or Atlanta. Yes, they were ‘free’ in the North, but were still considered second-class citizens to many in the North. They still did not have the right to vote nor were they allowed in the same establishments as whites. This is why the majority of blacks stayed in the South when the war started. They stayed to fight for their homeland against the ‘Yankees’. There was between 50,000 to 100,000 blacks that served in the Confederate Army as cooks, blacksmiths, and yes, even soldiers. Hollywood would have us believe that the Union Army first started letting Blacks fight with the movie “Glory”, the story of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. This is not the case. Here is the history of these brave souls.

There are many references to the trials that blacks had to endure during this era. Not many though, tell the story of blacks that served in the Confederacy. Although it is true that a good number of slaves fled to the North, there were those that chose to stay in the South to stay with their families or to fight what they saw as the tyranny of the Yankees. There is the story of a slave whose name were Silas Chandler and his master Andrew Chandler. (www.37thtexas.org) Andrew enlisted in the 44th Mississippi Volunteer Regiment and took Silas along with him as many Southerners did. Andrew was 15 years old and Silas was nearly 17 and very close friends with Andrew. Silas traveled between the plantation in Mississippi and wherever Andrew was. Andrew wrote home on 31 Aug 1862, “If the Feds were to capture him, they might take him along with them.” “I greatly fear another raid, don’t let them catch Silas. Be sure to write when Silas gets home.”

Andrew was severely wounded in the Battle of Chickamauga. Army doctors were prepared to amputate his leg but Silas refused to let the doctors perform the operation. Instead, he used a piece of gold to buy whiskey, which he used to buy a bottle of whiskey to bribe the surgeons for Andrews release. He carried his master on his back and loaded him on a boxcar in Atlanta and better medical care. Andrew survived as a cripple and the two remained friends for the rest of their lives and both received pensions for serving in the war.

On the far side of Arlington National Cemetery, in a little known place, is the cemetery’s largest monument. It is the Confederate Memorial that stands over the graves of Confederate Soldiers. On this monument is a carving of a black soldier, not in chains, but in a Confederate uniform marching along side his fellow soldiers. The sculptor of this monument was Moses Ezekiel. A Confederate veteran who knew what the true history of the war was. Ezekiel himself was a minority in the Confederate Army being Jewish, so he knew some of the trials the blacks were facing in the country. He was a native Virginian who graduated from the Virginia Military Institute and fought in the Battle of New Market where several black Confederates saw action. (www.37thtexas.org)

Although the Confederates did not officially enlist blacks until March 1865, some states allowed them to serve on a local level as early as 1861. Nobody really knows how many blacks actually served in the Confederacy; some estimates go as high as 50,000. A Union officer noted in his diary shortly before the Battle of Sharpsburg:

“Wednesday, September 10: At 4 o’clock this morning the Rebel army began to move from our town, (Fredrick, Md), Jackson’s forces taking the advance. The movement continued until 8 o’clock pm, occupying 16 hours. The most liberal calculation could not give them more than 64,000 men. Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. They were supplied with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc and they were an integral portion of the Southern Confederate army. They were seen riding on horses and mules, driving wagons, riding on caissons, in ambulances, with the staff of generals and promiscuously mixing it up with all the Rebel horde.” (Union Sanitation Commission Inspector Dr. Louis Steiner, Sept. 1862.)

Another Black Confederate is Levi Miller, a former slave who became a Confederate hero. He was one of thousands of slaves who went to war with their masters as a body servant. He was voted by his regiment to be a full-fledge soldier after nursing his master back from a near fatal wound. He also exhibited bravery in battles in Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. During the fighting at Spotsylvania Courthouse, his former commander, Capt. J.E. Anderson, said of him, “Levi Miller stood by my side and no man fought harder and better than he did when the enemy tried to cross our little breastworks and we clubbed and bayoneted them off, no one used his bayonet with more skill and effect than Levi Miller. During several battles, Levi met several other Negroes that he knew either by friendship or as a relative. They attempted to get him to desert to the North, but would not.

Upon his death, it is ironic that his coffin was draped with the Stars and Bars at a hero’s funeral service. He was laid to rest in a black cemetery. This is perhaps the biggest irony of all since the cemetery is near the spot where R.E. Lee is buried.

In a letter dated 27 March 1865, Lt. Col. Charles Marshall wrote a letter to Lt. Gen. Ewell stating that Gen. Lee regretted the “unwillingness of owners to permit their slaves to enter the service”, and “His only objection to calling them colored troops was that the enemy had selected that designation for theirs”. Also, “Harshness and contemptuous or offensive language or conduct to them must be forbidden and they should forget as soon as possible that they were regarded as menials”.

The following is a list of 4 soldiers captured at Ft. Fisher when it fell to Union troops in January 1865:

Charles Dempsey, Private, Company F, 36th NC Regiment, Negro. Captured at Ft. Fisher and confined at Point Lookout, Md., until paroled and exchanged at Coxes Landing, Va. 14-15 Feb 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

Henry Dempsey, Private, Company F, 36th NC Regiment, Negro. Captured at Ft. Fisher and confined at Point Lookout, Md., until paroled at Coxes Landing, Va. 14-15 Feb 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

J. Doyle, Private, Company E, 40th NC Regiment, Negro, Captured at Ft. Fisher and confined at Point Lookout, Md., until paroled at Boulware’s Wharf, Va. On 16 Mar 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

Daniel Herring, Cook, Company F, 36th NC Regiment, Negro. Captured at Ft. Fisher, and confined at Point Lookout, Md. Until released after taking Oath of Allegiance June 19, 1865. (Taken from North Carolina Troops, Volume I)

Notice that all 4 soldiers were black and that one of them signed an Oath of Allegiance only after Lee’s surrender.

If you look at the make up of Union troops, you can plainly see that blacks were segregated into separate units, while in the South, they were mixed in with the white troops. They were also given the same pay and rations as other Confederate troops as opposed to their counterparts in the North. In June 1861, Tennessee became the first state in the South to allow the use of black soldiers. The governor authorized the enrollment of those between the ages of 15-50 and have the same rations and clothing as white soldiers. Blacks started appearing in Tennessee regiments by September of that same year.

At the Battle of Fair Oaks near Richmond, a black cook and minister with the Alabama regiment picked up a rifle and was heard yelling, “Der Lor’ hab mercy on us all, boys, here dey comes agin!” As the Alabamians returned fire and mounted a charge, he was heard shouting, “Pitch in white folks, Uncle Pomp’s behind yer. Send them Yankees to de ‘ternal flames!” (Battlefields of the South. Vol. 2, page 253)

There are many stories about Black Confederates. I have listed only a few to give you a glimpse at them. There are many resources to go to and read if you wish to learn more. History can no longer be covered up by the ‘do-gooders’ that wish to wash our minds of the truth. I know where the hatred for the Confederate Battle Flag comes from, and it is not from the Old Confederacy. It comes from those who chose to degrade the good names of Confederate Soldiers. What they don’t realize though is that what they are hiding behind in the name of racial purity was fought and died for by men of all races; including blacks.

BIBILOGRAPHY FOR ROLES OF BLACKS IN THE CONFEDERATE ARMY

www.37thtexas.org. – The Black and the Gray

Washington City Paper-July 17, 1998

Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia by Ervin L. Jordan, Jr. (Charlottesville, Va: University Press of Virginia

Calico, Black and Gray: Women and Blacks in the Confederacy by Edward C. Smith, Civil War Magazine, Vol. VIII, No. 3, Issue XXIII, pg. 14

Battlefields of the South – Vol. 2

North Carolina Troops, Volume I

The Official Louisiana Tourism website – www.crt.state.la.us/crt/tourism/civilwar/overview.htm

Andersonh1

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 13, 2019

- Messages

- 580

- Reaction score

- 742

I'm sure he based his opinion on some information he's come across, but I don't know what it is. I would like to, certainly.'Conspiracy theories' are a form of 'belief'.

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

'Conspiracy theories' have some element of truth, they are not entirely fiction.I'm sure he based his opinion on some information he's come across, but I don't know what it is. I would like to, certainly.

Is there any evidence such a conspiracy existed? If so why has no evidence of said conspiracy been published? Oh, the conspiracy prevents the publication of evidence and thus proves the conspiracy.

'It's a conspiracy' sounds better than 'there is no evidence'.

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

http://www.flatfenders.com/scv/bc.htm

Welcome Compatriots!

to Camp 1745's

Black Confederates Page

Sons of Confederate Veterans

Orange, Texas

in beautiful Southeast Texas

21st Century Black Confederates

Thomas Nast's "Black Soldier" print

Black slaveowners

http://www.flatfenders.com/scv/beaner1219@yahoo.com

Membership info

website: chevelle@flatfenders.com

Amos Rucker---A Soldier Remembered

By: Calvin E. Johnson, Jr., Author of

When America stood for God, Family and Country.

1064 West Mill Drive

Kennesaw, Georgia 30152

Phone: 770 428 0978

Remember the American soldiers who defend our great nation.

A article recently appeared in a Charlotte, North Carolina newspaper about Wary Clyburn, a Black Confederate, who will be remembered on August 26, 2007 during a reunion of his descendants in Monroe, North Carolina. August 10th will also mark the 102nd anniversary of the death of a Black Confederate, Amos Rucker, of Atlanta, Ga.

Black Confederates, why haven't we heard more about them?

"I don't want to call it a conspiracy to ignore the role of the Blacks, both above and below the Mason-Dixon Line, but it was definitely a tendency that began around 1910"---Ed Bearrs, National Park Service Historian

Is American history still taught in our schools?

Today, the news focus is on Michael Vick's troubles and Barry Bond's home runs. In 1905, newspapers led with the opening of Woolworth's stores, the Atlanta, Ga. Terminal Railroad Station dedication with the US Army Band playing "Dixie."..... And on August 10th, Atlanta grieved the loss of a beloved soldier.

The movie "Glory" enlightened people of the role played by African-Americans serving in the Union Army during the War Between the States, 1861-1865.

And books like, "Forgotten Confederates---An Anthology about Black Southerners" by Charles Kelly Barrow, J.H. Segars and R.B. Roseburg, further enlightened us to the role played by African-Americans who served the Confederacy. (webmaster note: It has been republished in 2004, as "Black Confederates". The book lists many black Confederate soldiers and support personnel, with solid proof.)

Frederick Douglas, abolitionist and former slave, reported, "There are at present moment many colored men in the Confederate Army doing their duty not only as cooks, but also as real soldiers, having muskets on their shoulders and bullets in their pockets."

Who was Amos Rucker?

Amos Rucker, born in Elbert County, Georgia, was a servant of Alexander "Sandy" Rucker and both joined the 33rd Georgia Regiment of the Confederate Army. Amos got his first taste of battle when a fellow soldier was killed by a Union bullet. Rucker quickly took the dead soldier's rifle and fired back at the enemy.

After the War Between the States, Amos Rucker came back to Atlanta where he met and married Martha and the couple was blessed with many children and grandchildren.

In Atlanta, Amos joined the W.H.T. Walker Camp of the United Confederate Veterans. It was made up of Southern Veterans whose purpose was to remember those who served in the war and help those in need. The meetings were held at 102 Forsyth Street in Atlanta where Amos was responsible for calling the roll of members.

Amos and Martha felt that the members of Walker Camp were like their own family. It is written that Amos would say, "My folks gave me everything I want." These UCV men helped Amos and his wife buy a house on the west side of Atlanta and John M. Slaton also helped prepare a will for Rucker. Slaton, a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Gordon Camp, would, as governor of Georgia, commute the death sentence of Leo Frank.

Amos Rucker's last words to members of his UCV Camp were, "Give my love to the boys."

His funeral services were conducted by preacher and former Confederate General Clement A. Evans. Rucker was buried with his Confederate gray uniform and wrapped in his beloved Confederate Battle Flag. Today, some members of the Martin Luther King family are buried near Amos and Martha at Southview Cemetery.

The Reverend T.P. Cleveland led the prayer and when Captain William T. Harrison read the poem, "When Rucker Called The Roll" there was not a dry eye among the crowd of many Black and White mourners.

The grave of Amos and Martha Rucker was without a marker for many years until 2006, when the Sons of Confederate Veterans remarked it.

Did you know that the first military monument, near our nation's Capitol, to honor an African-American soldier is the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery?

"When you eliminate the Black Confederate soldier, you've eliminated the history of the South."---quote by the late Dr. Leonard Haynes, Professor, Southern University, or some say it was General Lee in 1864. Good quote, whoever said it.

Lest We Forget!!!

======================================================

================================================

Frederick Douglas wrote: “There are at the present moment, many colored men in the Confederate Army doing duty not only as cooks, servants, and laborers, but as real soldiers, having muskets on their shoulders and bullets in their pockets, ready to shoot down loyal troops and do all that soldiers may do to destroy the Federal government and build up that of the traitors and rebels. “

================================================

How did blacks serve in Gen. N.B. Forrest's command? The most reliable military resource concerning the Civil War documents their real roles.

"The forces attacking my camp were the First Regiment Texas Rangers [8th Texas Cavalry, Terry's Texas Rangers, ed.], Colonel Wharton, and a battalion of the First Georgia Rangers, Colonel Morrison, and a large number of citizens of Rutherford County, many of whom had recently taken the oath of allegiance to the United States Government. There were also quite a number of negroes attached to the Texas and Georgia troops, who were armed and equipped, and took part in the several engagements with my forces during the day." — Federal Official Records, Series I, Vol XVI Part I, pg. 805, Lt. Col. Parkhurst's Report (Ninth Michigan Infantry) on Col. Forrest's attack at Murfreesboro, Tenn, July 13, 1862.

........................................................................................................................

Letter to the Editor in Midland, TX by Col. Kelley

I called Principal Winget's office yesterday and sent the following Email to him of which he acknowledged receipt to help him prepare for this meeting:

...I am aware of the hearing that has been instigated regarding certain of the symbols, names and traditions associated with your school. I wish to offer my aid in preparing you to discuss this matter based on historical fact to counter Ms. Templeton's emotions.

As a Civil War historian and Texas Confederate reenactor I am well aware that Ms. Templeton's "offense" is the result of lack of knowledge of history and the resultant failure to understand the topic about which she is so highly motivated. Like many people on both sides of the issue she is operating from a position of emotion, belief and assumption rather than a solid grounding in historical fact.

Ms. Templeton specifically suffers from a lack of education or understanding of the nature of the Confederate States of America and the Confederate Army, especially the Confederate Army of Texas. She demands that her misconceptions become the rule by which others must conduct their lives.

The Union Army was strictly segregated and remained so until 1950. During the Civil War all non-whites were compelled to serve in "United States Colored Troop" regiments - this included Blacks, mulattos, Hispanics, Indians and anyone who was simply not "white enough." Often recruiting of Black Southerners for these regiments involved hunting them down, capturing them and even torturing them to get them to "volunteer" as documented in the Federal Official Records.

The Union Army had used Irish immigrants as "cannon fodder" to absorb the highest casualties in battle so Northern sentiments would not turn against the war being waged for economic domination of the agrarian South which provided 70% of the Federal budget. When the supply of "Micks" ran low they turned to the USCT to die in droves:

"...As usual with the enemy, they posted their negro regiments on their left and in front, where they were slain by hundreds, and upon retiring left their dead and wounded negroes uncared for, carrying off only the whites, which accounts for the fact that upon the first part of the battle-field nearly all the dead found were negroes." - Federal Official Records, Vol. XXXV, Chapter XLVII, pg. 341 - Report of Lieutenant M. B. Grant, C. S. Engineers, Savannah, April 27, 1864 - Battle of Ocean Pond (Olustee)

U.S. Grant issued "General Orders No. 11" in December, 1862, which expelled "all Jews, as a class" from his area of operations. It so disaffected his men that Jewish Union officers resigned en masse.

The Confederate Army included in its unsegregated combat ranks: 13,000 Indians, including Cherokee Chief and Confederate Brigadier General Stand Watie; 6200 Hispanics, 19% of them officers, nine of them Colonels and Texas Col. Santos Benavides who was so successful his area of Texas was known as "The Texas Benavides Confederacy;" 3500 Jews, including among the first and last Confederate officers to fall in battle and the Confederate Secretary of State, a Jewish lawyer from New Orleans; Filipinos from Lousiana whose ancestors were brought there by Spanish colonists before there was any African slave trade; tens of thousands of immigrants from all over the world; two Amerasian sons of Chang and Eng, the original "Siamese Twins," who served with Virginia cavalry and were both wounded in battle; and an as yet undetermined but significant number of Black Confederate combat soldiers, some of them regularly enlisted, who saw combat from the first battles of the war to the last as documented in the Federal Official Records, European newspapers, Northern and Southern newspapers and the letters and diaries of Union and Confederate soldiers.

"Almost fifty years before the (Civil) War, the South was already enlisting and utilizing Black manpower, including Black commissioned officers, for the defense of their respective states. Therefore, the fact that Free and slave Black Southerners served and fought for their states in the Confederacy cannot be considered an unusual instance, rather continuation of an established practice with verifiable historical precedence." - "The African-American Soldier: From Crispus Attucks to Colin Powell" by Lt. Col [Ret.] Michael Lee Lanning

In March, 1861, President Buchanan and President-Elelct Lincoln supported and lobbied for the passage of the "Corwin Amendment," a proposed 13th Amendment to the Constitution.

"Article Thirteen: No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State." - Submitted to the Senate by Corwin and supported by President-Elect Lincoln as the proposed 13th Amendment to the Constitution as voted on by that body on February 28th, 1861. The Senate voted 39 to 5 to approve this section passed by the House 133-65 on March 2, 1861. Two State legislatures ratified it: Ohio on May 13, 1861; and followed by Maryland on January 10, 1862. Illinois bungled its ratification by holding a convention.

- Joined

- May 12, 2019

- Messages

- 7,143

- Reaction score

- 4,164

http://www.flatfenders.com/scv/bc.htm

In December, 1862, only two months before Lincoln issued the "Emancipation Proclamation" (which freed not a single slave) in his State of the Union Address Lincoln offered the Confederacy a plan of gradual compensated emancipation with slavery not ending completely until 1900.

In comparison, your school's namesake had made his position clear some years before:

"There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil. It is idle to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it is a greater evil to the white than to the colored race." - Col. Robert E. Lee, United States Army, December 27, 1856

Offered the opportunity to come back into the Union successful in preserving slavery before a single shot was fired the Confederacy maintained its independence. Offered another chance to have 37 years to wean itself from slavery the Confederacy again maintained its independence.

The South did not secede nor did it fight to maintain slavery. The real issues were taxation, Federal revenues and national economics:

"The South has furnished near three-fourths of the entire exports of the country. Last year she furnished seventy-two percent of the whole...we have a tariff that protects our manufacturers from thirty to fifty persent, and enables us to consume large quantities of Southern cotton, and to compete in our whole home market with the skilled labor of Europe. This operates to compel the South to pay an indirect bounty to our skilled labor, of millions annually." - Daily Chicago Times, December 10, 1860

"They (the South) know that it is their import trade that draws from the people's pockets sixty or seventy millions of dollars per annum, in the shape of duties, to be expended mainly in the North, and in the protection and encouragement of Northern interest.... These are the reasons why these people do not wish the South to secede from the Union. They (the North) are enraged at the prospect of being despoiled of the rich feast upon which they have so long fed and fattened, and which they were just getting ready to enjoy with still greater gout and gusto. They are as mad as hornets because the prize slips them just as they are ready to grasp it." ~ New Orleans Daily Crescent, January 21, 1861

"...the Union must obtain full victory as essential to preserve the economy of the country. Concessions to the South would lead to a new nation founded on slavery expansion which would destroy the U.S. Economy." - Pamphlet No 14. "The Preservation of the Union A National Economic Necessity," The Loyal Publication Society, printed in New York, May 1863, by Wm. C. Bryant & Co. Printers.

"What were the causes of the Southern independence movement in 1860?

. . Northern commercial and manufacturing interests had forced through Congress taxes that oppressed Southern planters and made Northern manufacturers rich . . . the South paid about three-quarters of all federal taxes, most of which were spent in the North." - Charles Adams, "For Good and Evil. The impact of taxes on the course of civilization," 1993, Madison Books, Lanham, USA, pp. 325-327

Does Ms. Templeton think THESE Confederate soldiers would be "offended" by the Confederate links of your school?

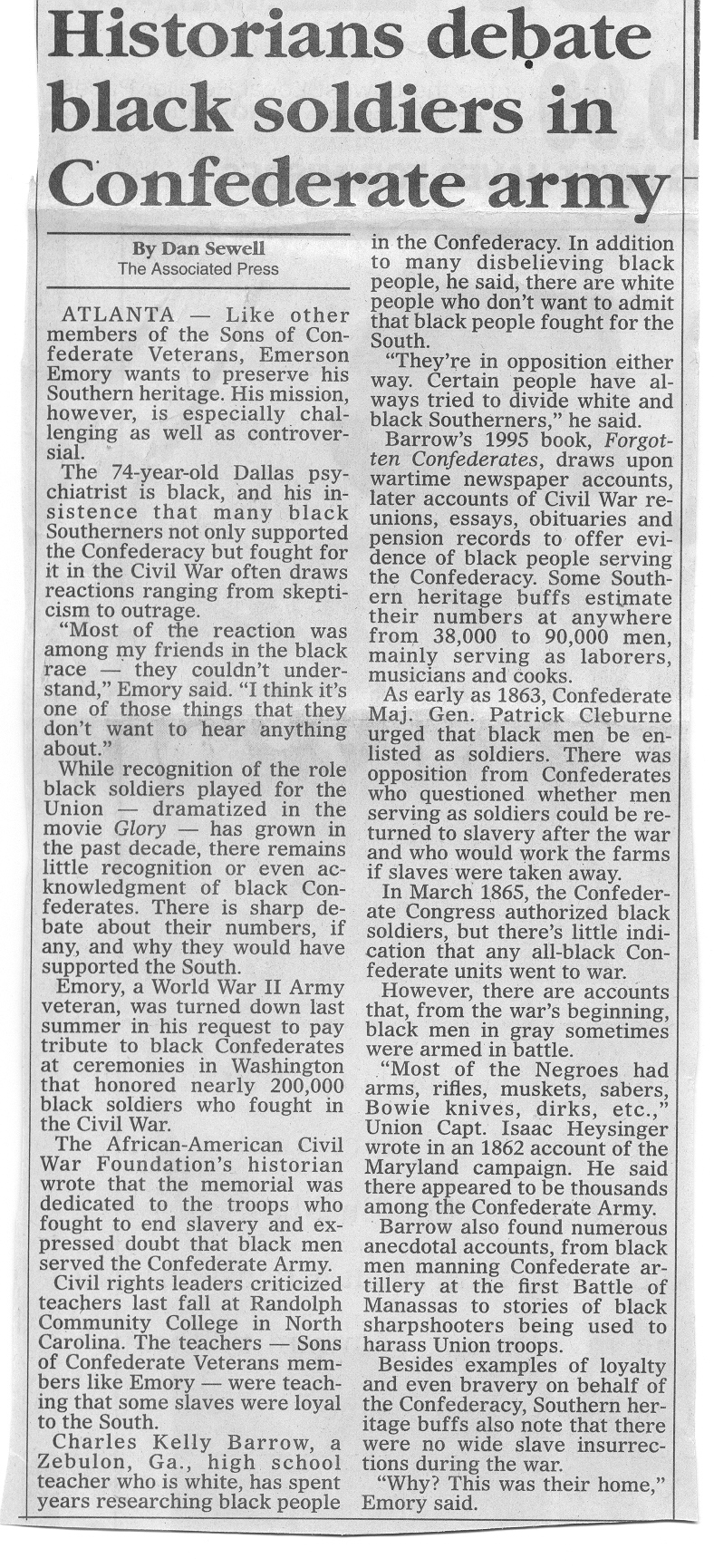

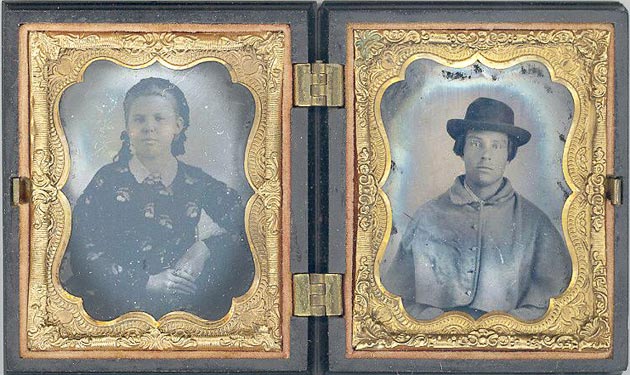

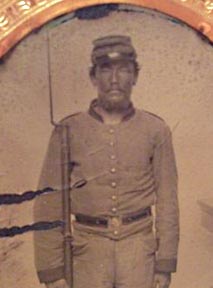

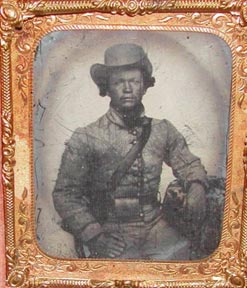

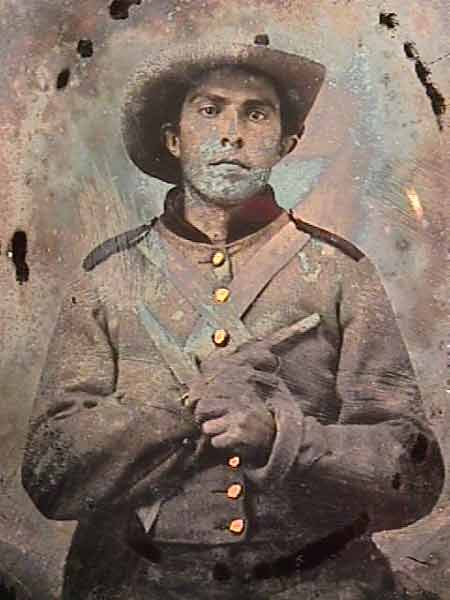

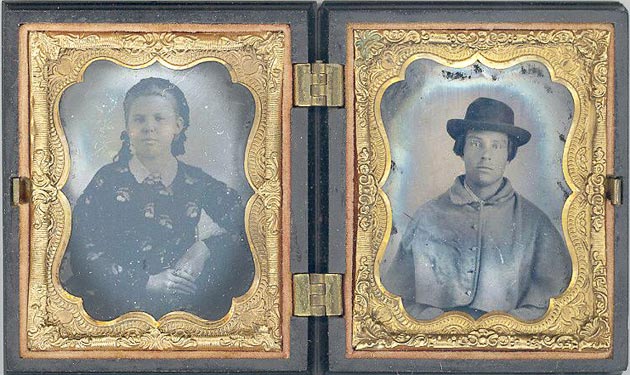

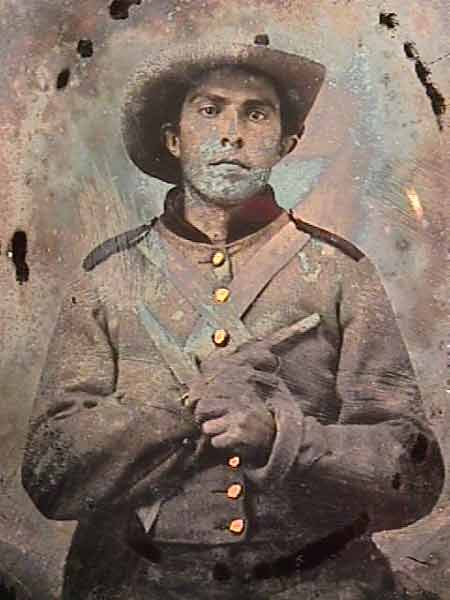

Andrew and Silas Chandler (Free Black), both regularly enlisted in the 44th Mississippi Infantry Silas saved Andrew's life at the Battle of Chickamauga

Mulatto Confederate Soldier Daniel Jenkins and his wife. Jenkins was with the Confederate 9th Kentucky Infantry and was killed at Shiloh on 4/6/62.

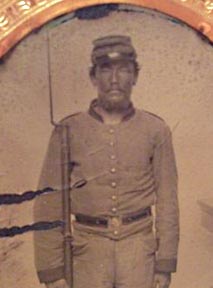

South Carolina Confederate Indian soldier

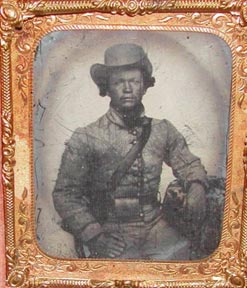

Private Marlboro, a free black Confederate Volunteer

Mixed-race Confederate

More specifically, would these Texas Confederate cavalry troopers be "offended" by your school's remaining Southern traditions or by Ms. Templeton's failure to know about them?

Ms. Templeton needs to significantly further her education before she discusses "being offended."

Perhaps Irish-born Confederate Major General Patrick Cleburne predicted it best in his January, 1864, letter which proposed the mass emancipation and enlistment of Black Southerners into the Confederate Army:

"Every man should endeavor to understand the meaning of subjugation before it is too late...It means the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern schoolteachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, and our maimed veterans as fit objects for derision...The conqueror's policy is to divide the conquered into factions and stir up animosity among them..."

Through painstaking research and thorough, uncommented documentation we celebrate the courage, sacrifice, and heritage of ALL Southerners who had to make agonizing personal choices under impossible circumstances.

"The first law of the historian is that he shall never dare utter an untruth. The second is that he shall suppress nothing that is true. Moreover, there shall be no suspicion of partiality in his writing, or of malice." - Cicero (106-43 B.C.)

We simply ask that all act upon the facts of history. We invite your questions.

Your Obedient Servant,

Colonel Michael Kelley, CSA

Commanding, 37th Texas Cavalry (Terrell's)

http://www.37thtexas.org

"We are a band of brothers!"

". . . . political correctness has replaced witch trials and communist hearings as the preferred way to torment our fellow countrymen." "Ghost Riders," Sharyn McCrumb, 2004, Signet, pp. 9

"I came here as a friend...let us stand together. Although we differ in color, we should not differ in sentiment." - Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, CSA, Memphis Daily Avalanche, July 6, 1875

Black Confederate Participation

by Tim Westphal

"...And after the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, ...reported among the

rebel prisoners were seven blacks in Confederate uniforms fully armed as

soldiers..."

- New York Herald, July 11, 1863. [1]

I. Introduction

As far back as the American Revolution, African Americans have fought in

every conflict this country has been engaged in. A number of authors have

studied the participation which blacks played for the Union and Confederate

governments during the Civil War. Most of these writers have focused on the

Union army since it employed a large number of blacks as soldiers during

the

conflict. "When authors do cover the Confederate side, they usually limit

their coverage to the free blacks of New Orleans who formed a regiment of

"Native Guards" for the Louisiana militia and the Confederate effort late

in

the war to employ slaves as soldiers" [2]. Civil War historians have not

given these blacks their due recognition, and have left the truth of their

involvement for the Confederacy covered in obscurity and confusion.

As many as 90,000 blacks, slave and free, were employed in some capacity by

the Confederate army. The majority of these men fall into two categories,

as

military laborers or body servants. The fact that some Southern blacks

might

have played an important role for the South is a very controversial issue.

Scholars have avoided the difficult task of linking any blacks to the

Southern war effort. One of the main reasons they choose not to attempt

this

is because they are afraid of confronting the great paradox that exists.

Why

would any slaves or free blacks work towards a Southern victory when this

war was seen as one to sustain blacks' enslavement and degradation? The

point of this paper is to seek out exactly what kind of role any blacks,

free or slave, served in the South during the war and to examine the

reasons

why they would support the Southern war cause.

The Louisiana Native Guards demonstrate what free blacks, from Louisiana,

thought about the Confederacy. The Louisiana Native Guards was a militia

regiment comprised of 1400 black men and officers, "who offered their

services to Dixie" in April of 1861 [3]. The following year 3000 black men

and officers organized themselves into the 1st Native Guard of Louisiana.

These pro-Confederate blacks formed for the protection of New Orleans.

After

parading through the city they were described in the newspaper as "rebel

Negroes...well drilled...and uniformed" [4]. Historians argue the Native

Guards were a unique circumstance. The difference between Louisiana and the

rest of the South was its peculiar tri-racial system. The state of

Louisiana

was home to a population, which was different than the rest of the

country's. The population consisted of many Spanish and "Creole" families.

It was easier for Louisiana to accept these men for military service. For

that reason historians like to separate the free "blacks" in that state

from

the rest of the free blacks in the South. Many other states had blacks

volunteer their services, and some states accepted these volunteers. There

were slaves in Alabama who were organized as soldiers in the fall of 1861.

There were also 60 free blacks in Virginia who formed their own company and

marched to Richmond to volunteer their services to help in the war effort.

"Several companies of free Negroes offered their services to the

Confederacy

Government early in the war" [5]. The War Department decided they wouldn't

be needed at this time so they sent them home.

II. Body Servants and Laborers

Body servants consisted of slaves or free blacks. They were between the

ages

of sixteen and sixty. They accompanied both Confederate soldiers and

officers into the war. "Body servants in a continuation of the master-slave

relationship, tended their wounded soldiers, sometimes escorting their

bodies home and occasionally fought in battles" [6]. The number of body

servants in the Confederate army was considerable in the early days of the

war. The jobs of the body servants varied greatly. An officer's servant was

expected to keep the officer's quarters clean, to wash the clothes, brush

uniforms, polish swords and buckles, and to run errands, such as going to

the commissary and getting rations. The servant was supposed to look after

his master's horse, making sure it was well groomed and well fed. It was

the

duty of one of these servants to have the horse ready in the morning by the

time the officer was ready to ride.

Slaves who came from plantations with their owners were the most loyal

under

difficult incidents. "Negroes who had been treated well before the start of

the war were more faithful during the most trying days of the conflict"

[7].

In many cases, soldiers and servants had been childhood playmates. The

result of this was a genuine affection for each other, which further

cemented during the shared hardships brought on by the war. "No other

slaves

had as good opportunities for desertion and disloyalty as the body

servants,

but none were more loyal" [8].

A personal servant would have been chosen from among the slaves that had

been affiliated with the family for a long time. For that reason these

slaves often felt a responsibility for the protection of their master when

going into the war. The owners of body servants respected the devotion and

loyalty displayed by their black servants. "Owners frequently made

provisions for their servants freedom, and after the war blacks dressed in

'Confederate Gray' were among the most honored veterans in attendance at

soldiers reunions" [9].

In December, 1862, only two months before Lincoln issued the "Emancipation Proclamation" (which freed not a single slave) in his State of the Union Address Lincoln offered the Confederacy a plan of gradual compensated emancipation with slavery not ending completely until 1900.

In comparison, your school's namesake had made his position clear some years before:

"There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil. It is idle to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it is a greater evil to the white than to the colored race." - Col. Robert E. Lee, United States Army, December 27, 1856

Offered the opportunity to come back into the Union successful in preserving slavery before a single shot was fired the Confederacy maintained its independence. Offered another chance to have 37 years to wean itself from slavery the Confederacy again maintained its independence.

The South did not secede nor did it fight to maintain slavery. The real issues were taxation, Federal revenues and national economics:

"The South has furnished near three-fourths of the entire exports of the country. Last year she furnished seventy-two percent of the whole...we have a tariff that protects our manufacturers from thirty to fifty persent, and enables us to consume large quantities of Southern cotton, and to compete in our whole home market with the skilled labor of Europe. This operates to compel the South to pay an indirect bounty to our skilled labor, of millions annually." - Daily Chicago Times, December 10, 1860

"They (the South) know that it is their import trade that draws from the people's pockets sixty or seventy millions of dollars per annum, in the shape of duties, to be expended mainly in the North, and in the protection and encouragement of Northern interest.... These are the reasons why these people do not wish the South to secede from the Union. They (the North) are enraged at the prospect of being despoiled of the rich feast upon which they have so long fed and fattened, and which they were just getting ready to enjoy with still greater gout and gusto. They are as mad as hornets because the prize slips them just as they are ready to grasp it." ~ New Orleans Daily Crescent, January 21, 1861

"...the Union must obtain full victory as essential to preserve the economy of the country. Concessions to the South would lead to a new nation founded on slavery expansion which would destroy the U.S. Economy." - Pamphlet No 14. "The Preservation of the Union A National Economic Necessity," The Loyal Publication Society, printed in New York, May 1863, by Wm. C. Bryant & Co. Printers.

"What were the causes of the Southern independence movement in 1860?

. . Northern commercial and manufacturing interests had forced through Congress taxes that oppressed Southern planters and made Northern manufacturers rich . . . the South paid about three-quarters of all federal taxes, most of which were spent in the North." - Charles Adams, "For Good and Evil. The impact of taxes on the course of civilization," 1993, Madison Books, Lanham, USA, pp. 325-327

Does Ms. Templeton think THESE Confederate soldiers would be "offended" by the Confederate links of your school?

Andrew and Silas Chandler (Free Black), both regularly enlisted in the 44th Mississippi Infantry Silas saved Andrew's life at the Battle of Chickamauga

Mulatto Confederate Soldier Daniel Jenkins and his wife. Jenkins was with the Confederate 9th Kentucky Infantry and was killed at Shiloh on 4/6/62.

South Carolina Confederate Indian soldier

Private Marlboro, a free black Confederate Volunteer

Mixed-race Confederate

More specifically, would these Texas Confederate cavalry troopers be "offended" by your school's remaining Southern traditions or by Ms. Templeton's failure to know about them?

Ms. Templeton needs to significantly further her education before she discusses "being offended."

Perhaps Irish-born Confederate Major General Patrick Cleburne predicted it best in his January, 1864, letter which proposed the mass emancipation and enlistment of Black Southerners into the Confederate Army:

"Every man should endeavor to understand the meaning of subjugation before it is too late...It means the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern schoolteachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, and our maimed veterans as fit objects for derision...The conqueror's policy is to divide the conquered into factions and stir up animosity among them..."

Through painstaking research and thorough, uncommented documentation we celebrate the courage, sacrifice, and heritage of ALL Southerners who had to make agonizing personal choices under impossible circumstances.

"The first law of the historian is that he shall never dare utter an untruth. The second is that he shall suppress nothing that is true. Moreover, there shall be no suspicion of partiality in his writing, or of malice." - Cicero (106-43 B.C.)

We simply ask that all act upon the facts of history. We invite your questions.

Your Obedient Servant,

Colonel Michael Kelley, CSA

Commanding, 37th Texas Cavalry (Terrell's)

http://www.37thtexas.org

"We are a band of brothers!"

". . . . political correctness has replaced witch trials and communist hearings as the preferred way to torment our fellow countrymen." "Ghost Riders," Sharyn McCrumb, 2004, Signet, pp. 9

"I came here as a friend...let us stand together. Although we differ in color, we should not differ in sentiment." - Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, CSA, Memphis Daily Avalanche, July 6, 1875

Black Confederate Participation

by Tim Westphal

"...And after the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, ...reported among the

rebel prisoners were seven blacks in Confederate uniforms fully armed as

soldiers..."

- New York Herald, July 11, 1863. [1]

I. Introduction

As far back as the American Revolution, African Americans have fought in

every conflict this country has been engaged in. A number of authors have

studied the participation which blacks played for the Union and Confederate

governments during the Civil War. Most of these writers have focused on the

Union army since it employed a large number of blacks as soldiers during

the

conflict. "When authors do cover the Confederate side, they usually limit

their coverage to the free blacks of New Orleans who formed a regiment of

"Native Guards" for the Louisiana militia and the Confederate effort late

in

the war to employ slaves as soldiers" [2]. Civil War historians have not

given these blacks their due recognition, and have left the truth of their

involvement for the Confederacy covered in obscurity and confusion.

As many as 90,000 blacks, slave and free, were employed in some capacity by

the Confederate army. The majority of these men fall into two categories,

as

military laborers or body servants. The fact that some Southern blacks

might

have played an important role for the South is a very controversial issue.

Scholars have avoided the difficult task of linking any blacks to the

Southern war effort. One of the main reasons they choose not to attempt

this

is because they are afraid of confronting the great paradox that exists.

Why

would any slaves or free blacks work towards a Southern victory when this

war was seen as one to sustain blacks' enslavement and degradation? The

point of this paper is to seek out exactly what kind of role any blacks,

free or slave, served in the South during the war and to examine the

reasons

why they would support the Southern war cause.

The Louisiana Native Guards demonstrate what free blacks, from Louisiana,

thought about the Confederacy. The Louisiana Native Guards was a militia