5fish

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jul 28, 2019

- Messages

- 10,757

- Reaction score

- 4,577

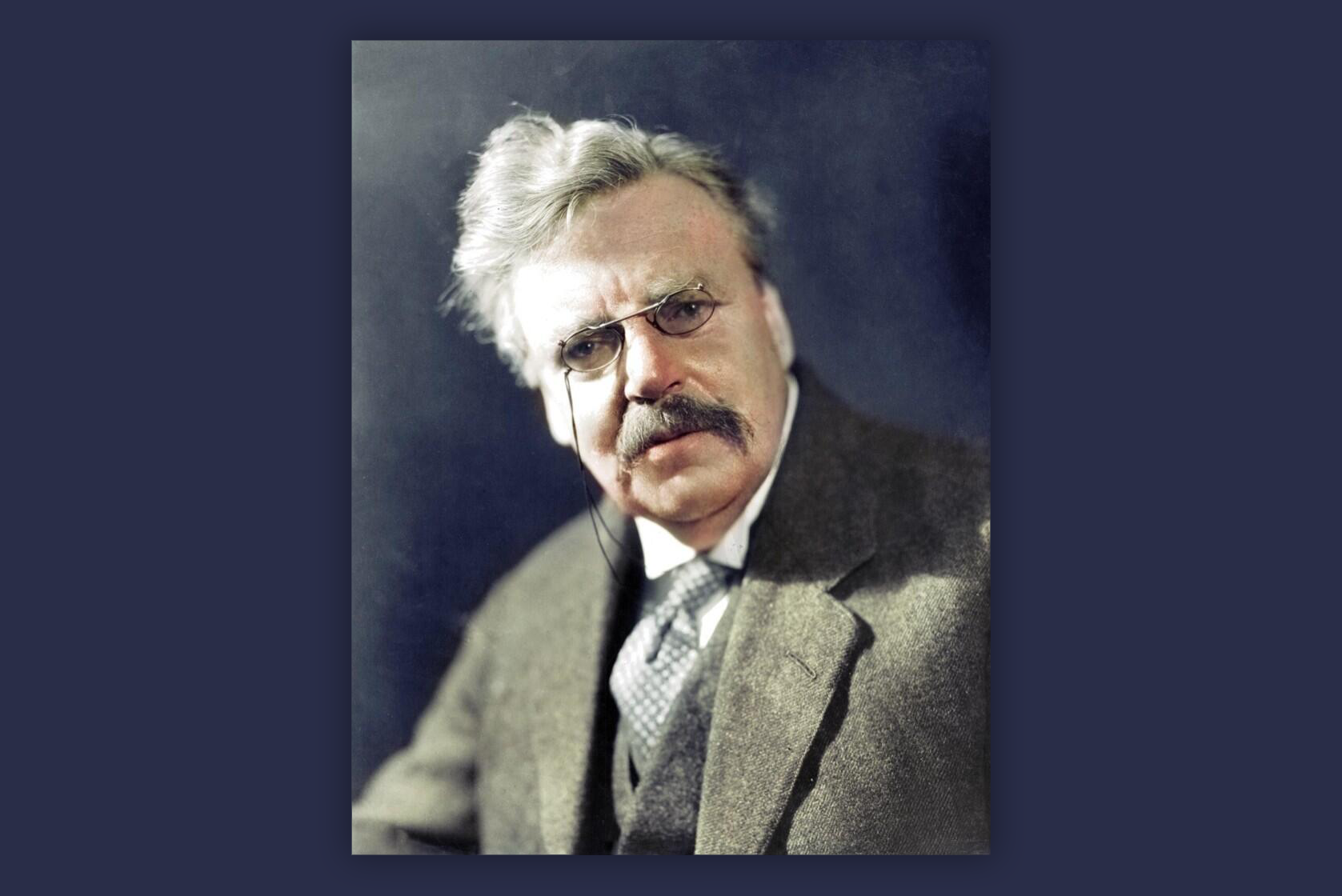

Chesterton had a great influence over two of the greatest fantasy writers of the 20th century. He influenced Tolkien and Lewis with the writings they read during WW 1. He influenced Lewis so much that it brought him back to Christianity. Magic must mean something...

theimaginativeconservative.org

.

theimaginativeconservative.org

.

Although it is evident that Tolkien and Lewis were well-versed in Chesterton’s work, the essay of his which was probably most influential on the philosophy of myth that underpinned their own approach to story-telling was “The Ethics of Elfland,” which formed the fourth chapter of Chesterton’s book, Orthodoxy.

Another facet of Chesterton’s “Ethics of Elfland” which would prove inspirational to Tolkien and Lewis was Chesterton’s insistence that myths and fairy stories were not unbelievable, in the sense that they conveyed untruths, but were the most believable things in the world because they conveyed truths and taught lessons that the world needed to know and learn:

It will also remind lovers of Tolkien and Lewis of the Great Music of God’s Creation in The Silmarillion and of Aslan’s singing of Narnia into being. And as for Chesterton’s proclamation that “this world of ours has some purpose” and that “magic must have a meaning, and meaning must have someone to mean it,” it leads us into the words of Gandalf, whose words of encouragement to Frodo will serve as appropriately encouraging words with which to conclude our musings on the magic of Elfland:

Chesterton, Tolkien and Lewis in Elfland

G.K. Chesterton’s insistence that myths and fairy stories were not unbelievable, in the sense that they conveyed untruths, but were the most believable things in the world because they conveyed truths and taught lessons that the world needed to know and learn, would prove inspirational to J.R.R...

theimaginativeconservative.org

theimaginativeconservative.org

Although it is evident that Tolkien and Lewis were well-versed in Chesterton’s work, the essay of his which was probably most influential on the philosophy of myth that underpinned their own approach to story-telling was “The Ethics of Elfland,” which formed the fourth chapter of Chesterton’s book, Orthodoxy.

Another facet of Chesterton’s “Ethics of Elfland” which would prove inspirational to Tolkien and Lewis was Chesterton’s insistence that myths and fairy stories were not unbelievable, in the sense that they conveyed untruths, but were the most believable things in the world because they conveyed truths and taught lessons that the world needed to know and learn:

It will also remind lovers of Tolkien and Lewis of the Great Music of God’s Creation in The Silmarillion and of Aslan’s singing of Narnia into being. And as for Chesterton’s proclamation that “this world of ours has some purpose” and that “magic must have a meaning, and meaning must have someone to mean it,” it leads us into the words of Gandalf, whose words of encouragement to Frodo will serve as appropriately encouraging words with which to conclude our musings on the magic of Elfland: